“A heartfelt and beautifully written homage to Scholfield-Peters’ forebears, who were caught in the 20th century horrors of fascism and anti-semitism, and, in her loving portrait of her grandfather, to the survival of the human spirit. A moving contribution to the literature of the Shoah and its ricochet effect down the generations.”

Australian stories are part of the Holocaust. A granddaughter writes: he ‘knew he was lucky’ to escape, but paid a high price by Jan Lanicek for The Conversation.

Scholfield-Peters balances on the line between fact and fiction. She reconstructs the family history for herself, in the memory of her beloved grandfather and his parents, who she never met. Sources to reconstruct Harry’s life are limited, because he only occasionally shared details about his life before and during the war.

Harry left behind a briefcase with letters his parents sent to him at the time of his emigration and during his first months in Australia. But the correspondence includes only the letters Harry received, which silences the other half of the story. We will never know what Harry wrote back. After the outbreak of the war, Max, Edith and Oma only sent a few short messages, up to 25 words per message, via the Red Cross. Then they turned silent.

In 1997, Harry recorded a video testimony for the Shoah Foundation. Scholfield-Peters uses all these snippets of information to bring her great-grandparents and her grandfather, Harry, back to life. She tries to imagine how they personally experienced the episodes mentioned in the letters, depicted in photos Harry brought with him to Australia, or recollected by Harry later in his life. This is how Scholfield-Peters gets to know her relatives who perished in the Holocaust.

She struggles with the process of searching, concerned she is intruding into personal affairs that should possibly remain buried in the past. She knows what lies ahead for them, but cannot do anything to save them, or reassure Max and Edith that their son will do well in Australia.

Read full review here.

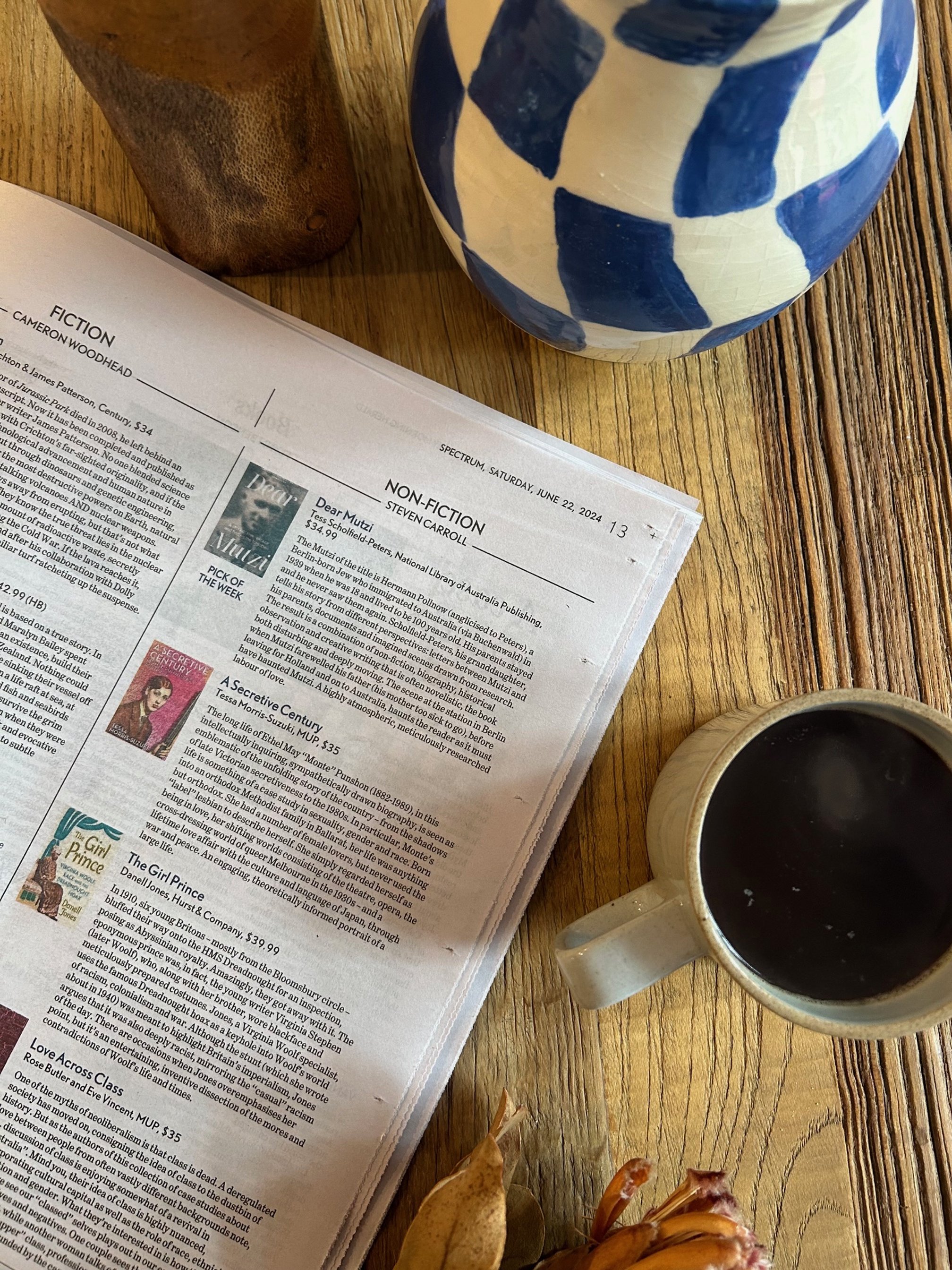

The Mutzi of the title is Hermann Pollnow (anglicised to Peters), a Berlin-born Jew who immigrated to Australia (via Buchenwald) in 1939 when he was 18 and lived to be 100 years old. His parents stayed and he never saw them again. Scholfield-Peters, his granddaughter, tells his story from different perspectives: letters between Mutzi and his parents, documents and imagined scenes drawn from research. The result is a combination of non-fiction, biography, historical observation and creative writing that is often novelistic, the book both disturbing and deeply moving. The scene at the station in Berlin when Mutzi farewelled his father (his mother too sick to go), before leaving for Holland and on to Australia, haunts the reader as it must have haunted Mutzi. A highly atmospheric, meticulously researched labour of love.

Steven Carroll, Non-Fiction Pick of the Week in Sydney Morning Herald (originally published 22 June 2024).

Tess Scholfield-Peters’ debut book, Dear Mutzi, is a narrative nonfiction account of her grandfather’s experience in Nazi Germany. It powerfully describes how 18-year-old Hermann Pollnow fled Nazi Germany for rural Australia and became Harry Peters. Mutzi was the affectionate nickname given to Hermann by his devoted parents, Max and Edith, who perished in Nazi camps. Scholfield-Peters uses a combination of letters written by Hermann’s father during the 1930s, interviews with her grandfather and present-day narrative from her third-generation perspective to tell this striking story. She skillfully portrays Hitler’s ascendency and the destruction of German Jewry, the increasing persecution the family faced, and the extent of Edith’s and Max’s love for Hermann, which is palpable through their letters and gives the book a poignant and emotionally charged tone. The author’s evocation of European landscapes illustrates the beauty of Germany, in contrast to Hermann’s first impression of the Australian landscape: ‘The smell of recent rain on the eucalypts was strange. The dense bushland and the browns and greys were nothing like the forests of Germany.’ Dear Mutzi goes beyond a personal family history with its themes of involuntary migration, adaptation into Australian society, and resilience, and will strike a chord with readers interested in the history of this period or who have enjoyed historical fiction by Heather Morris.

Katy Briggs, Books & Publishing (review originally published here).

This felt very close to me: it’s about an Australian grandpa, born in the 1920s in Berlin. I had one of those, and I called him Opi, and I loved him dearly. Tess Scholfield-Peters had one, too. She called him Mutzi. As a teenager, he fled Germany and came to Australia. His parents, who stayed behind, were murdered in Nazi concentration camps. This book is the result of years of painstaking research. A labour of love, for sure, but this man’s story will feel so very real to so many Australians whose families came from Europe after the war.

Caroline Overington, The Weekend Australian (originally published in ‘Notable Books’ 15 June 2024.